The United States swiftly closed ranks with its ally South Korea on Monday, as the death of nuclear-armed North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-Il landed President Barack Obama with a sudden foreign policy crisis.

Obama called his close friend President Lee Myung-Bak of South Korea at midnight on the US east coast, as Washington and its regional allies digested the death of the Stalinist state’s volatile 69-year-old leader.

“The President reaffirmed the United States’ strong commitment to the stability of the Korean peninsula and the security of our close ally, the Republic of Korea,” the White House said in a statement.

“The two leaders agreed to stay in close touch as the situation develops and agreed they would direct their national security teams to continue close coordination,” the statement added.

In an earlier first reaction to Kim’s death from a heart attack, announced on Pyongyang’s official media, a careful White House said it was “closely monitoring” the situation in a nation with a history of belligerence.

It said Washington had been in touch with Japan, as well as South Korea.

A State Department official said that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was also briefed on the death of Kim, as the US national security machine buzzed into life late on a Sunday night.

There was no direct word from Obama, who is locked in a domestic political showdown over taxes with Republicans which was already likely to delay his annual Christmas and New Year vacation in his native Hawaii.

US officials declined to be drawn into discussions of the US diplomatic or military response to Kim’s death or its geopolitical implications.

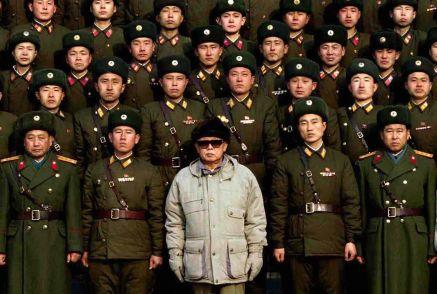

They were aware that Kim, who ruled ruthlessly, shackling his own people with his personality cult and confining them to famine and poverty, had been ill, and that a political transition was under way in Pyongyang.

But privately, they have expressed concern about Kim’s chosen successor, his third son Kim Jong-Un, and admit their knowledge of the isolated state’s next ruler is limited.

There will be concern in Washington over the stability of the government in Pyongyang, and over the unpredictable state’s next steps as Kim Jong-Un seeks to cement his control.

A US lawmaker with a lead role on Asia policy was less circumspect than Obama administration officials after hearing of Kim’s demise, from what the North Korea KCNA agency said a myocardial infarction and heart attack.

“Kim Jong-Il was the epitome of evil, a dictator of the worst kind who ruled his country with an iron fist and dished out constant pain and misery to his people,” said Republican Representative Don Manzullo, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs subcommittee on East Asia.

“We hope his passing will mark a new chapter for North Korea. This is an opportunity for North Korea to emerge from its cycle of oppression and walk down a new path toward democracy,” he said.

Former State Department spokesman Philip J. Crowley warned on his Twitter feed meanwhile that uncertain days could lie ahead in northeast Asia.

“There may be some provocations for a while as he looks to prove himself,” Crowley wrote on Twitter.

“If North Korea were a normal country, the death of Kim Jong-Il might open the door to a Pyongyang Spring. But it is not a normal country,” he wrote.

Obama’s White House has repeatedly stressed there is no daylight between it and its allies South Korea and Japan on policy towards North Korea.

Obama has forged one of his closest relationships with a foreign leader with Lee, partly as an overt sign to Pyongyang that there is little point seeking to drive a wedge between Washington and Seoul.

Kim’s death came as North Korea and the United States were making tentative efforts to restart stalled six-nation talks on the North’s nuclear program.

Nuclear envoys from Washington and Pyongyang met in New York in July and in Geneva in October, but reported no breakthrough. South Korea’s Yonhap news agency said that a third meeting could have taken place soon.

Obama warned North Korea in October that it would face deeper isolation and international pressure if it carried out more “provocations” like those that rattled Asia last year.

But as he met Lee at the White House, the US leader said Pyongyang could however expect greater opportunities if it lived up to its international obligations over its nuclear program.

The North quit the six-party forum, which involves the United States, China, the two Koreas, Japan and Russia, in April 2009, a month before staging its second nuclear test.

The North wants the forum to resume without preconditions and says its uranium enrichment program — first disclosed to visiting US experts one year ago — can be discussed at the talks.