Although a fully-equipped medical evacuation aircraft with a trained crew and pilot will likely always be the best option to get a wounded Soldier off the battlefield, the Army is looking at unmanned aerial systems as a possible “plan B” for when that ideal isn’t possible.

“There’s really a lot of opportunity to be gained if we learn how to leverage these unmanned systems for medical missions, as a tool to augment our existing medical assets,” said Nathan Fisher, an engineer with the Army’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center at Fort Detrick, Maryland.

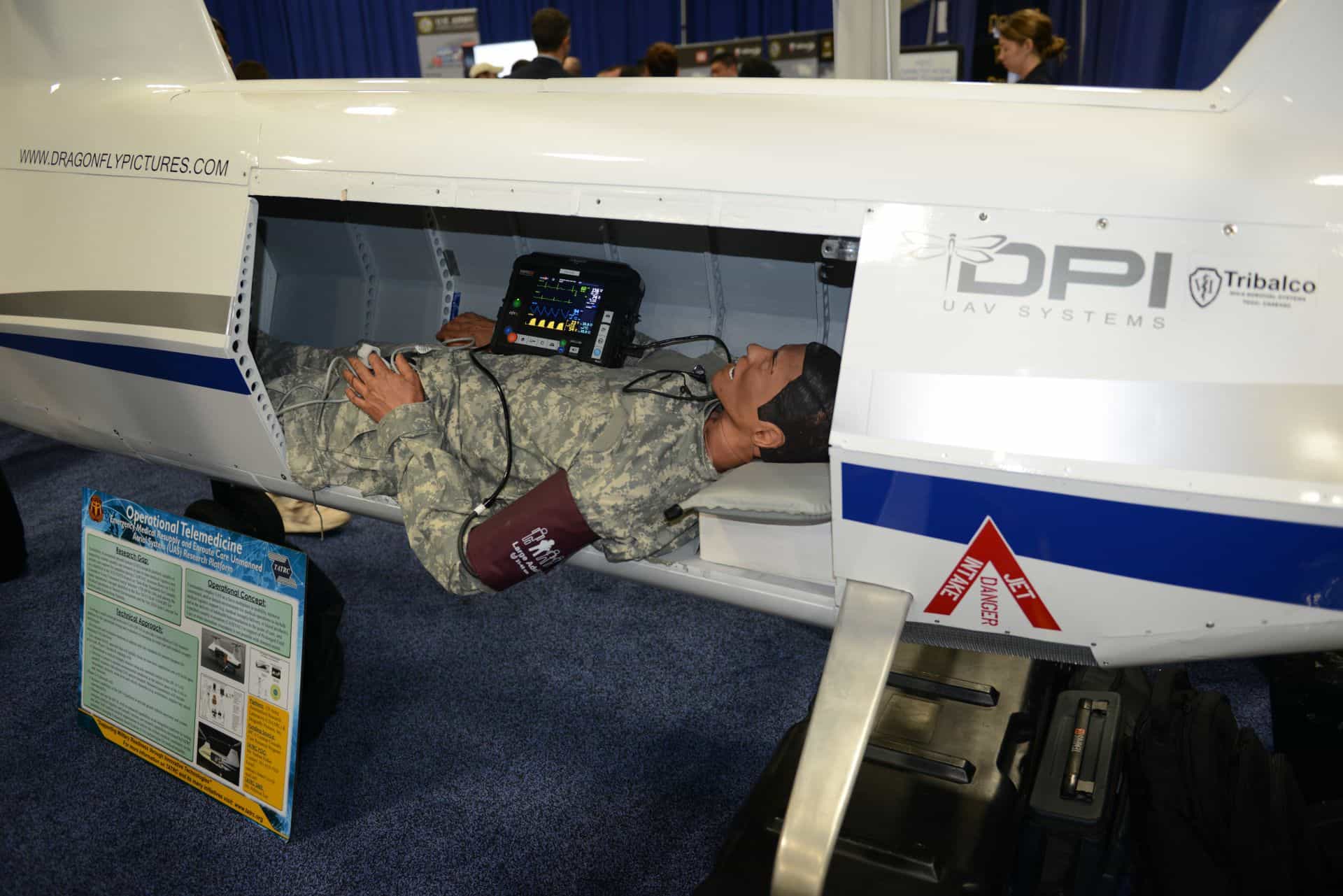

Fisher was available Oct. 10 during the Association of the U.S. Army Annual Meeting and Exposition. On the display floor of the convention center, where hardware from hundreds of defense contractors was being showcased, he discussed research he and others are involved in that may one day make it possible to deliver medical supplies to the battlefield by UAS, and to also send that UAS back to base with a wounded Soldier tucked away safely inside.

FUTURE DEMAND AUTONOMY

During last year’s AUSA exposition, Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. Mark A. Milley laid out a nearly apocalyptic vision of what Soldiers would face on battlefields of the future.

Milley told Soldiers they should plan on being miserable, that access to supplies would be limited, and that they should expect lines of communication between themselves and those in the rear to be nearly non-existent. When those lines of communication open, a robotic supply convoy might end up being “the only acceptable method of supply that we can get to forward troops.”

It’s that kind of environment that Fisher and fellow researchers at TATRC are developing solutions for today.

“In situations where we’re up against a near-peer type adversary in a complex environment, like in a megacity for example — we’re tasked to support these dispersed units from a medical perspective,” Fisher said. “It boils down to a situation where air superiority is not something that we can assume. At least not for an extended period of time. So how do we support these units from a medical perspective?”

Two types of support in particular are of concern to Fisher. First, how to get medical supplies out to the field if no aircraft or crew are available, or if the flying conditions won’t permit it. Second, how to get wounded Soldiers from the field back to treatment facilities in the rear, without using manned aircraft.

To help the Army one day provide both of those kinds of support, TATRC is making use of a UAS called the DP-14 “Heavy Fuel Tandem Helicopter” as a platform to test concepts and work out the issues associated with unmanned resupply and unmanned medical evacuation.

Fisher said the dual-rotor DP-14 was chosen as a testbed because, among other things, it can carry a 450-pound payload, it has a small footprint, and it can do vertical take-off and landing. All make it ideal to deliver goods, or retrieve injured Solders from just about anywhere.

NO HUMANS ALLOWED … YET

The Army has yet to fly a human inside its DP-14, and may actually never do that, Fisher said. Right now, it’s not permissible to fly persons inside unmanned systems, at least not in the U.S.

One of the things TATRC is working on now, Fisher said, is instrumenting the DP-14 to determine what conditions might be like inside the UAS if a patient were to actually ride inside it. What they want to discover, he said, is if a UAS like the DP-14 can be built to support human life while in the air.

Using a system he called the “Environmental Factors Data Acquisition System,” they are measuring factors like shock, vibration, noise, temperature, pressure, acceleration, and pitch of the aircraft. All are factors that affect how safe it will be to put a person inside. He said a similar test will be done on the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, which is already used to do medical evacuations, to establish a baseline for what is permissible.

Then, he said, they will “really start determining, in a quantitative way, what’s the difference in exposure levels,” and then look for ways to mitigate the difference.

Fisher also said that putting a patient inside a UAS will require some form of patient-support system be available, and that system will need to transmit patient data to caregivers on the ground. Developing those systems, or configuring existing systems for life aboard a UAS is also part of their project.

EASY ON THE MEDIC

Another issue associated with using a UAS for casualty evacuation — or even for supply delivery — is ensuring that its operation doesn’t become a burden on the Army medics who are most likely to be its primary users.

“Kind of the general problem that we run into is that you have a combat medic out there in the field providing care,” Fisher said. “And they are really focused on the patient and they need to remain focused on the patient, both cognitively and with the use of their hands. How do you introduce technology in that environment without diverting attention away from providing care?”

The UAS must be truly autonomous, Fisher said, such that the medic only interacts with them in a kind of “supervisory role.”

“What’s the field interface with the medic, and how do they interact with the vehicle?” Fisher asked. “And how do we provide them with situational awareness, and a limited amount of command and control, just to do that high-level interaction?”

Fisher suggested that the kinds of interaction a medic might need to have with the UAS would be limited to something as simple as providing an indicator that it’s safe for the UAS to land, versus waving it off.

When it comes to casualty evacuation, Fisher said, “The ideal scenario is that you have a medevac platform in there with a dedicated medical crew that can take care of a patient while flying en route. That’s always plan A.”

But if it’s not possible to get a medevac crew to a location, Fisher said, then a UAS may end up one day being the solution.

“I like to call it a plan B,” he said. “It’s a situation where you can’t get a medevac there in time, or there’s no medevac assets available due to the threat situation or due to the fact that they are just at capacity.”