WEST POINT: When Lt. Col. Jason Barnhill traveled to Africa last summer, he took with him not only the normal gear of an Army officer, but also a 3D printer.

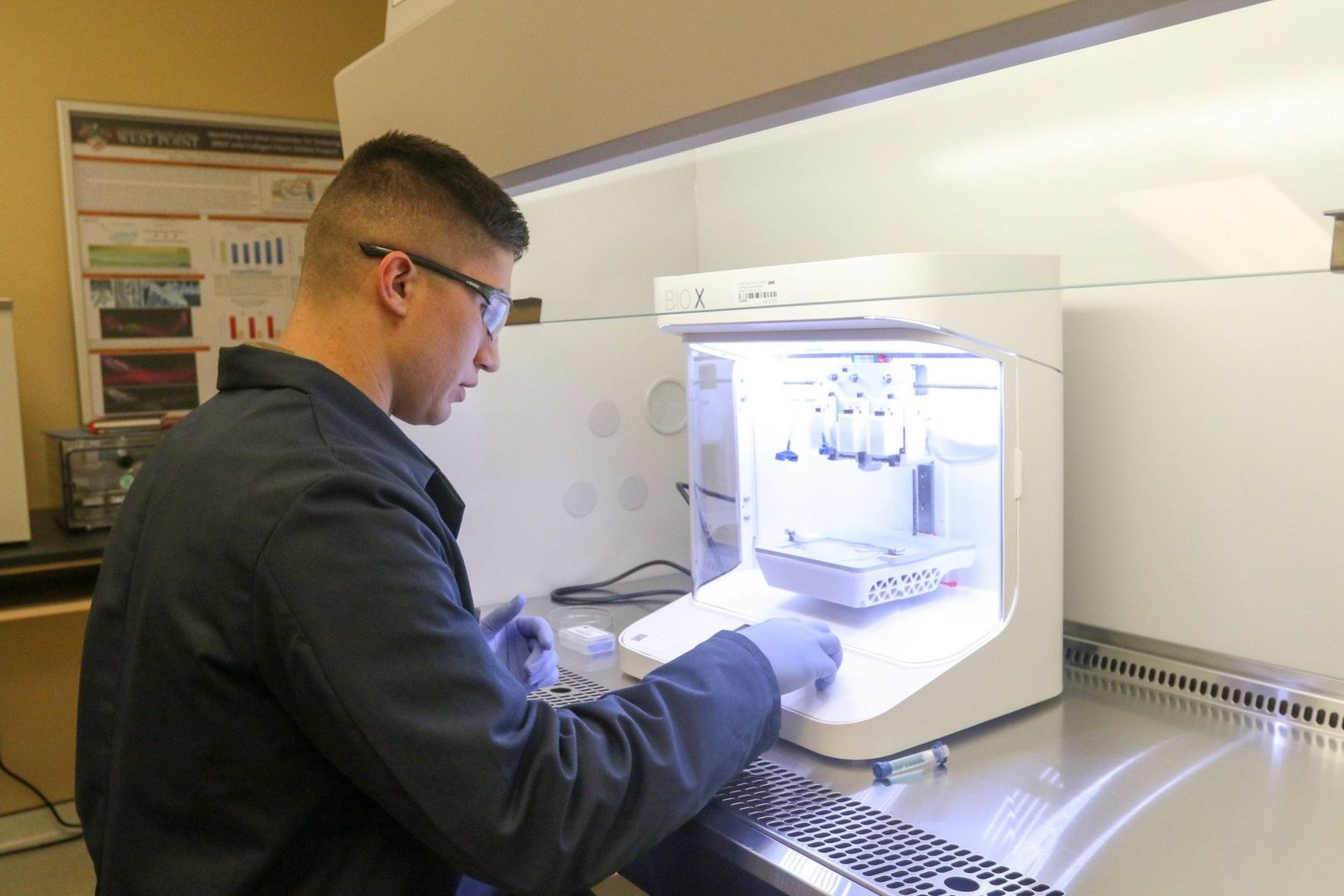

Barnhill, who is the life science program director at the U.S. Military Academy, traveled to Africa to study how 3D printers could be used for field medical care. Barnhill’s printer was not set up to print objects made out of plastics as the printers are frequently known for. Instead, his printer makes bioprinted items that could one day be used to save Soldiers injured in combat.

The 3D bioprinting research has not reached the point where a printed organ or meniscus can be implanted into the body, but Barnhill and a team of cadets are working to advance the research in the field.

Twenty-six firsties are doing bioprinting research across seven different projects as their capstone this year. Two teams are working on biobandages for burn and field care. Two teams are working on how to bioengineer blood vessels to enable other bioprinted items that require a blood source, such as organs, to be viable. One team is working on printing a viable meniscus and the final team is working on printing a liver.

The basic process of printing biomaterial is the same as what is used to print a plastic figurine. A model of what will be printed is created on the computer, it is digitally sliced into layers and then the printer builds it layer by layer. The difference is the “ink” that is used.

Instead of heating plastic, 3D bioprinting uses a bioink that includes collagen, a major part of human tissue, and cells, typically stem cells.

“A lot of this has to do with the bioink that we want to use, exactly what material we’re using as our printer ink, if you will,” Class of 2020 Cadet Allen Gong, a life science major working on the meniscus project, said. “Once we have that 3D model where we want it, then it’s just a matter of being able to stack the ink on top of each other properly.”

Cadets are researching how to use that ink to create a meniscus to be implanted into a Soldier’s injured knee or print a liver that could be used to test medicine and maybe one day eliminate the shortage of transplantable organs.

The research at West Point is funded by the Uniformed Services University of Health Science and is focused on increasing Soldier survivability in the field and treating wounded warriors.

Right now, cadets on each of the teams are in the beginning stages of their research before starting the actual printing process. The first stage includes reading the research already available in their area of focus and learning how to use the printers. After spring break, they will have their first chance to start printing with cells.

For the biobandage, meniscus and liver teams, the goal is to print a tangible product by the end of the semester, though neither the meniscus or liver will be something that could be implanted and used.

“There are definitely some leaps before we can get to that point,” Class of 2020 Cadet Thatcher Shepard, a life science major working on the meniscus project, said of actually implanting what they print. “(We have to) make sure the body doesn’t reject the new bioprinted meniscus and also the emplacement. There can be difficulties with that. Right now, we’re trying to just make a viable meniscus. Then, we’ll look into further research to be able to work on methods of actually placing it into the body.”

The blood vessel teams are further away from printing something concrete because the field has so many unanswered questions. Their initial step will be looking at what has already been done in the field and what questions still need to be answered. They will then decide on the scope and direction of their projects. Their research will be key to allowing other areas of the field to move forward, though. Organs such as livers and pancreases have been printed, so far, they can only be produced at the micro level because they have no blood flow.

“It’s kind of like putting the cart before the horse,” Class of 2020 Cadet Michael Deegan, a life science major working on one of the blood vessel projects, said. “You’ve printed it, great, but what’s the point of printing it if it’s not going to survive inside your body? Being able to work on that fundamental step that’s actually going to make these organs viable is what drew me and my teammates to be able to do this.”

While the blood vessel, liver and meniscus projects have the potential to impact long-term care, the work being done by the biobandage teams will potentially have direct uses in the field during combat. The goal is to be able to take cells from an injured Soldier, specifically one who suffers burns, and print a bandage with built in biomaterial on it to jumpstart the healing process.

Medics would potentially be deployed with a 3D printer in their Humvee to enable bandages to be printed on site to meet the needs of the specific Soldier and his or her exact wound. The projects are building on existing research on printing sterile bandages and then adding a bioengineering element. The bandages would be printed with specialized skin and stem cells necessary to the healing process, jumpstarting healing faster.

“We’re researching how the body actually heals from burns,” Class of 2020 Cadet Channah Mills, a life science major working on one of the biobandage projects, said. “So, what are some things we can do to speed along that process? Introducing a bandage could kickstart that healing process. The faster you start healing, the less scarring and the more likely you’re going to recover.”

The meniscus team is starting with MRI images of knees and working to build a 3D model of a meniscus, which they will eventually be able to print. Unlike a liver, the meniscus doesn’t need a blood flow. It does still have a complex cellular structure, though, and a large part of the team’s research will be figuring out how and when to implant those cells into what they’re printing.

Of the 26 cadets working on bioprinting projects, 17 will be attending medical school following graduation from West Point. The research they are doing gives them hands-on experience in a cutting-edge area of the medical field. It also enabled them to play a role in improving the care for Soldiers in the future, which will be their jobs as Army doctors.

“Being on the forefront of it and just seeing the potential in bioengineering, it’s pretty astounding,” Gong said. “But it has also been sobering just to see how much more complicated it is to 3D print biomaterials than plastic.”

The bioprinting projects will be presented during the academy’s annual Projects Day April 30.