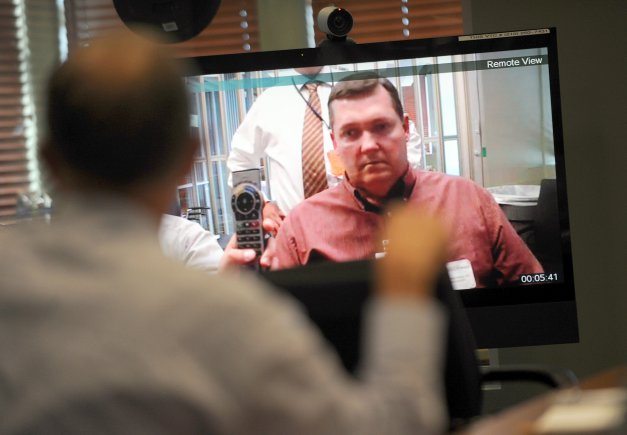

Imagine being a psychologist sitting across from your patient.

Now imagine that patient is actually hundreds of miles away.

The first-ever live Introduction to Telemental Health Delivery Workshop at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology’s, or T2, headquarters on Joint Base Lewis-McChord last week offered guidance to providers on offering mental health services from a distance — in this case, using videoconferencing technology.

“The (Department of Defense) is pushing for this form of care because it’s a way to reach a lot of people who otherwise wouldn’t get care,” T2 clinical health psychologist Dr. Greg Kramer said.

Kramer was one of the all-day workshop’s presenters. About 25 health care professionals from every military branch attended the training, some coming from as far away as Japan. The idea was to build a knowledge base so that clinicians can provide care even when their patient is too far to get to.

The session included information on the history of teletechnology in health care, addressed legal concerns and gave them the chance to practice videoconferencing with each other.

“It allows them to get comfortable with the technology,” Kramer said.

In fact, the use of remote technology in mental health care is relatively new. Efforts to incorporate it into DoD policies and procedures increased in the late 2000s.

Since then emphasis on these programs has increased, in hopes to better serve those who live in areas where there are shortages of mental health care providers. An estimated 87 million Americans live in places where care is scarce, and up to 25 percent of servicemembers screen positive for mental health concerns, according to T2’s Introduction to Telemental Health.

“This allows us to provide things like telepsychiatric appointments especially in rural and high needs areas,” T2 clinical telehealth division chief Dr. Jamie Adler said.

The technology can be used in a variety of ways, from treating post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to wellness and resiliency interventions.

Of course, the new medium for care comes with some specific quirks. Participants at the workshop got a taste of technical difficulties when T2’s network went down briefly during the training. Other issues had to do with clinical practice — for instance, if a patient appears to be avoiding eye contact, it’s more likely that they’re looking at the face on the computer screen instead of the video camera.

Many of the attendees had already begun using teletechnology to provide services to patients at off-site locations, but the rare in-person training (as opposed to online sessions) gave providers the chance to learn about and discuss technical, legal and clinical elements of providing telemental health care.

“I took some notes that I think are valid points for implementing this,” said Dr. Agnes Babkirk, a psychologist from U.S. Naval Hospital in Okinawa, Japan.

She’s bringing that information back to her colleagues, who currently use teletechnology to interact with patients three or four times a week.

Dr. Daniel Christensen, the chief of Madigan’s Soldier Readiness Service, had a similar experience. The service has been using teletechnology for post-deployment behavioral health screenings since March of this year. He said the training validated the practices they already had in place.

In the future, psychologists at T2 hope to offer more trainings, and expand them to reach providers at different levels. For instance, separate sessions for those considering using teletechnology, beginners and experienced clinicians.

For more information, including a Telemental Health Planning and Implementation Guide, visit http://t2health.org/programs-telehealth.html.