The Age, As the blame game gets increasingly ugly, experts are pondering Australia's choices in the global war on terrorism.

George Bush's unexpected Thanksgiving visit to Baghdad was a much-needed fillip for US forces in Iraq. The symbolism will play extremely well in America. But for all the dramatic impact of the President's party trick, it won't mask growing anxiety internationally about where all this will end.

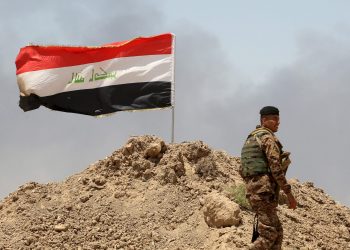

Throughout the holy month of Ramadan, Saddam loyalists and Islamists combined in a tag-team of terror against coalition troops and Iraqi civilians. This was accompanied by a vicious wave of suicide bombings in Turkey and Saudi Arabia, indicating al-Qaeda's continuing capacity to sow strife in the Arab and Islamic worlds.

Meanwhile, the “blame game” is getting increasingly ugly.

It isn't the US deploying ambulances to blow up aid workers in Iraq, just as it wasn't Bush who sent passenger jets plummeting into New York two years ago.

Yet it is American power, and its impact on the world, that has become the singular preoccupation for many engaged in debate on the breakdown of the global order.

This week, the new Lowy Institute for International Policy convened its first conference in Sydney to ponder the choices Australia has made in supporting the US-led war on terror.

What were the implications of this costly and arduous undertaking for America? Has Iraq backfired? Was Australia's high-profile involvement serving its interests as a middle power in this part of the world, and how is support for the US playing with the neighbours? The verdict, on weight of voices, was flattering neither to the Howard Government nor to US policy under President Bush.

The gathering included prominent strategic analysts such as Owen Harries and Bob O'Neill, respected former diplomats, Rawdon Dalrymple and Ross Garnaut, and an impressive rollcall of public intellectuals. Much of the discussion was off-the-record. But the predominant view to emerge was that both the US and Australia had some serious thinking to do about the long-term consequences of current strategy.

But, in the current uncertain climate, the tone of these debates sometimes tend towards the surreal.

Dr Hugh White, director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said the war on terror should be kept in perspective. Australia had faced a direct threat to its survival in 1942, wars and upheaval in South-East Asia in the 1960s, and the risk of nuclear warfare and global annihilation during the Cold War years. “Terrorism is not an existential threat on that scale,” he said, citing far greater dangers ahead if, for example, the US and China resumed head-butting over Taiwan.

In what has become the recurring theme of the foreign policy debate, many at the conference joined White in warning that Australian policy-makers had to be careful not to allow close ties with the superpower to cut across closer strategic engagement with Asia, where China, Japan and India also compete for influence.

Visiting Singaporean defence analyst Mark Hong warned of widespread consternation in the region over the Bush doctrine of pre-emption, especially in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Hong said any suggestion the US or its allies might arrogate to themselves the right to take the fight against Islamist terror across all borders was a matter of great sensitivity to the nations of South-East Asia, for whom “non-interference” is the first principle of international behaviour.

Several conference participants went on to proclaim the Bush Doctrine effectively dead. The grisly aftermath of war in Iraq was fast eroding popular support in the US, and the politics of an election year would force a pullback from the current “in-your-face”posture. The implication was that Australia should hasten to reposition itself, adopt a stance more in tune with its neighbours and use its standing as a trusted ally to pressure the US for a strategic reappraisal.

With an unpredictable North Korea presenting itself as the next big test for Washington, there is nothing wrong with urging the cautious calibration of policy. But, in the current uncertain climate, the tone of these debates sometimes tend towards the surreal.

Ugly realities have a habit of intruding. If, for example, al-Qaeda happened to succeed in launching a second catastrophic terror attack on US soil, all the talk today of keeping the superpower in check would count for little.