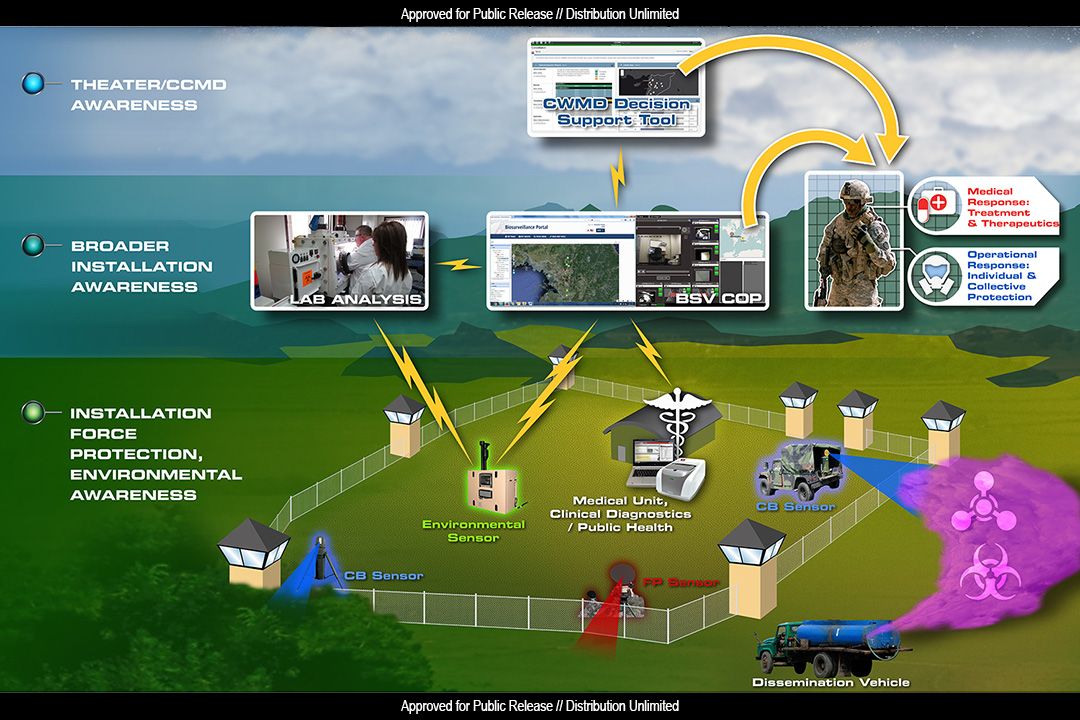

At U.S. military installations throughout the world, military police monitor force protection sensors, which consist of conventional and thermal imaging cameras, ground surveillance radar and seismic and acoustic sensors.

Installations also have chemical biological sensors, but they are operated as an independent system manned by chemical biological specialists in another location.

Project JUPITR’s early warning system aims at combining powerful surveillance tools into a single integrated system so military police and chemical biological specialists can immediately cross check their data and respond to incidents faster.

JUPITR, or Joint U.S. Forces in Korea Portal and Integrated Threat Recognition, is a three-year advanced technology demonstration of biosurveillance technology for deployment on the Korean Peninsula.

The leg is an assessment of 10 different biological agent detection technologies in the field to determine their speed, accuracy and suitability for a field environment.

In June 2015, a team of U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center’s, or ECBC’s, chemical biological specialists and Joint Project Manager, or JPM, Guardian software systems and hardware engineers performed an operational demonstration of a system of integrated force protection and chemical biological sensors on Osan Air Base, South Korea, with U.S. Army and Air Force military police and chemical biological specialists.

“We had a system called the Joint All-Hazards Common Control Station [JACCS] that we use in Afghanistan,” said Robert Bednarczyk, deputy product manager for Joint Product Manager Force Protection Systems and the leader of the early warning effort. “It features a common operating picture, which displays all the force protection sensor data on one screen.”

The team integrated the JACCS software to add additional data from chemical biological point sensors and standoff sensors to the JACCS common operating picture.

“We then held an exercise in which we simulated a threat,” he said. “The military police at their location and the chemical biological specialists at another location were all looking at the same common operating picture at the same time, and seeing the same data streaming in from both the force protection and chemical biological sensors in real time.”

This proved to be a vital improvement.

Military police were able to notify the chemical biological specialists that a suspicious vehicle was in the area. The chemical biological specialists were able to watch the truck on screen and notify the military police that a standoff chemical biological sensor had alarmed. That buys time, as much as three or four minutes depending on the distance, the wind and the configuration of the sensors. In that time, the base commander can be alerted and take charge of the response, base personnel can suit up in their personal protective equipment, and the Army and Air Force chains of command can be notified.

The technical demonstration was the culmination of 14 months of hard work by the ECBC-JPM Guardian team.

They had to select the right chemical biological sensors, which then had to be fully integrated into the JACCS system. Each of the eight sensors they selected spoke a slightly different language in computer terms. Establishing a common language required additional programming followed by interface testing, followed by more programming tweaks, and again, more interface testing.

“It was tedious and frustrating at times,” Bednarczyk said, “because it all came down to manipulating a staggeringly large number of ones and zeroes until the whole thing worked perfectly.”

This was followed by a three-month integration assessment at Dugway Proving Ground, Utah. The team set up the array of sensors to be in exactly the same relative position they would be in at the upcoming operational demonstration at Osan. They set the entire system up, tested it and broke it back down three different times, taking up to two weeks each time. They tested the system with simulants each time.

Adding to the complexity was the need for a very big work-around. They were unable to use chemical biological simulants at Osan due to local sensitivities. So the team had to configure its sensors and simulant release point using the exact same footprint they planned to use at Osan. The data from the Dugway exercise would then be used as the sensor feed to the common operating picture at the Osan technical demonstration. But, because the wind came predominately from the south at Dugway, and from the west at Osan, when they got to Osan they had to precisely rotate the entire configuration from south-facing to west-facing.

“Instead of the truck in the exercise releasing the simulant two kilometers to the south of the installation fence as at Dugway, at Osan we made it appear to be two kilometers to the west with all the sensors following that exact same rotation,” said John Strawbridge, chemical biological sensor lead for the project and an ECBC mechanical engineer. “We then had to recreate the truck drive-by at Osan with exactly the right timing.”

All that work proved worthwhile. The early warning system was a hit at the operational demonstration.

“The participants told us it was a vast improvement,” Bednarczyk said. “The military police look at the screens all the time as part of their job, to be able to bring in chemical biological specialists so fast and so completely the moment they saw something they suspected could involve chemical or biological agent was a big step forward in protecting the base.”