For a company of paratroopers planted in the heart of Taliban country, newly built Joint Security Station Hasan in southern Ghazni Province is a chance to make a real difference.

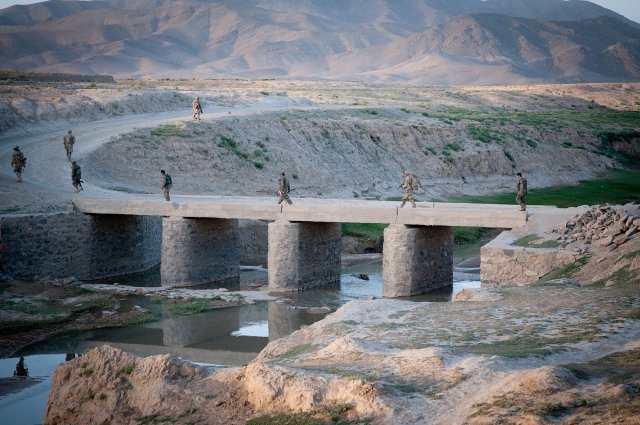

Conceived as a blockade against arms, explosives and fighters streaming up through Ghazni’s desolate Nawah District from Pakistan, JSS Hasan was established within view of the only bridge spanning the Tarnak River that is able to support heavy vehicles.

It’s plain “country” living, with no running water, electricity, hot meals, only ankle-deep dust, dry heat and daily bombardment from enemy mortars and rocket-propelled grenades.

The reaction from Taliban fighters to security forces moving into one of their primary support zones has been violent, according to Capt. Philip Schneider, whose company of 82nd Airborne Division paratroopers built the post in an old, burned-out compound in the village of Hasan and man it with Afghan soldiers of 3rd Brigade, 203rd Corps.

“We take contact every time we go out,” said Schneider, an armor officer who has spent nearly his entire career leading infantry, including a 15-month tour in Baghdad as part of the Surge.

“We didn’t get much contact when we were building, but after, it was game on,” he said. “We take indirect fire daily, and the road coming in here is full of [improvised explosive devices]. We’ve called in gun runs from A-10s and Apaches; we use danger-close artillery extensively and have had rounds fall within 200 meters of friendlies. The learning curve is very steep down here.”

Enemy fighters make extensive use of small-unit tactics, using motorcycles to efficiently navigate the irrigation ditches and dry wadis, deep-furrowed grape fields, tight village roads and maze-like kalats to set up ambush after ambush.

“These guys know how to shoot down here,” said Schneider. “They’re well-equipped. They have Japanese handheld radios, GPS and Iranian night vision binoculars. They are very effective in those first few moments, but it’s hard for them to sustain.”

LEVERAGING ASSETS

Schneider considers his strongest assets to be his Afghan National Army, or ANA, partners. The Afghan company commander, Capt. Jawid Ramin, comes from military stock. Brothers, a grandfather and uncles all served.

Ramin’s father and mother died in the Soviet war when he was just three. He was still in high school when NATO forces arrived in Kabul after Sept. 11, 2001, and he recalls fighting the Taliban in between classes.

Ramin performed so well in school and later in the National Military Academy that he was invited to lunch with then ISAF Commander Gen. Stanley McChrystal, and he was sent to the U.S. for further military training.

“He wanted to go to ranger school, but they wouldn’t let him,” said Schneider.

“He’s educated and he knows tactics, and he refuses to use his connections to attain rank or when he doesn’t agree with his chain of command,” he said.

The iconic figure at JSS Hasan, though, is the last of four brothers who have been killed fighting the enemies of Afghanistan, a 37-year-old platoon sergeant named Arabkhan.

“He’s like a Rambo,” said Schneider. “My Soldiers have a lot of respect for him. He’s tactically sound, as much as Rambo ever was, but he’s a storm-the-beaches kind of guy.”

Schneider told of flanking in a firefight, only to turn around and see Arabkhan leading a small element straight at the enemy, bullets hitting the ground all around him.

“He’s fearless,” said Schneider.

Arabkhan is a warrior, but also a preacher, and the Americans have found he has a way with words when speaking with village elders.

REACTION OF LOCALS

Most of the insurgents around the Tarnak River are fighters from Pakistan who make war for money not religion, according to Arabkhan.

“When we talk with villagers, I tell them I am a Muslim,” he said. “You are Muslim too. I am Afghan. You are also Afghan. Because of that, we should not allow Pakistan to soil our house. Everyone agrees with that.”

Locals are happy to see ANA in their villages, especially the women, who are beaten by Taliban if they’re not covered up enough, said Schneider.

“The Taliban come at night and strong-arm the villagers, sometimes locking them in their houses while they take their stuff. The ANA ask permission before entering a house.”

The locals hate the Pakistani fighters, but after 10 years of intimidation, they are afraid to fight for their community.

“You see no schools here, no clinics, no power, no water,” said Capt. Ramin, the ANA company commander. People live like barbarians in an ice age. They know that, if a person is educated, they are not joining the Taliban.”

The key to reclaiming the area, according to Schneider, is getting the villages to band together and stand up a local police force.

“If you have [Afghan Local Police] to establish checkpoints, it will relieve the burden on the ANA so they can push out and maneuver on the enemy,” explained Schneider.

Recently, his battalion commander, Lt. Col. Rob Salome, traveled to Hasan to meet with elders of the surrounding villages in hopes of getting them to commit to an ALP, and while progress was made in the aggregate — more village elders attended this time than the last — nobody wanted to be the first to make a stand.

To the north, the people of Andar District were fighting back and succeeding, Schneider reminded the elders.

“At least tell us when the Taliban are coming into the area so we can meet the enemy outside of town,” he asked them.

They would not commit, however, without the framework of a greater Gelan District security plan that included many more villages.

OUTSIDE THE WIRE

One element departed a few hours after midnight, moving east under night vision; a larger force left around four in the morning when the first farmers usually enter the fields. They linked up just outside the village of Spedar, the hometown of the local Taliban commander.

By seven, the paratroopers of Company D and their ANA counterparts were heavily engaged in a firefight, with dozens of rocket-propelled grenades smoking overhead in both directions.

In a heroic move to counter the enemy’s L-shaped ambush, a squad leader from San Diego led his fire team to high ground to lay a base of suppressive fire. A single 7.62 bullet pierced the chest of Staff Sgt. Nicholas Fredsti, knocking him to the ground. Medic Pfc. Michael Trevino rushed to the open ground, and while two riflemen and a machine gunner held off the attack, Trevino treated the wounded paratrooper, stopping every 30 seconds to help return fire on the enemy.

A show of force from a low-flying Air Force B-1 bomber helped curtail the enemy fire. After evacuating the wounded by helicopter, the allied forces moved into Spedar, led by Arabkhan and his Afghan soldiers.

On the far side of the village, they were fired upon again, this time from a lone grape hut separated from the village just enough to call in Apache helicopters for a gun run. Fire from the helicopters ended the engagement but also nicked Afghan soldiers who had moved too far ahead of the rest.

Though American medics moved quickly to treat their wounds, the close bonds between the American and Afghan fighters seemed to fray in an instant. Some of the Afghans swore they would never to fight alongside the Americans again. The Afghan first sergeant separated his men and led them away.

Still many miles from the security station, two lines of soldiers — Afghan and American — walked in parallel lines for some distance, but terrain, and eventually, a third and fourth firefight, brought them together again. The bonds they had forged from three weeks of guarding each others’ backs were simply too strong.

Like iron filings to a magnet, riflemen joined with riflemen, machine gunners with machine gunners, and together, they secured and crossed back over the exposed Tarnak River Bridge.

“Combat down here — jumping into the same grapefields for cover, returing fire on the same enemy — builds that bond,” said Schneider. There’s nothing that can replicate that.”

REWARDS AND LOSSES

By all accounts, Staff Sgt. Fredsti was one of the best squad leaders in the company and respected as a man whose priorities were unwavering. He is D Company’s first fatality in nearly three weeks of fighting.

“He led from the front. He was a hero,” said Sgt. Joshua Bracey, one of his subordinate team leaders.

His platoon leader, 1st Lt. Matthew Archuleta, said it was noncommissioned officers like Fredsti who make the U.S. Army the greatest in the world.

Far from flattened, the platoon was only resolved to make Fredsti’s loss worth the life their friend and comrade lived. They would mourn, and then they would take the fight back to the enemy.

The men of D Co. have put their hearts into the fight at JSS Hasan, but so have their Afghan counterparts, said Schneider. Ramin, who is engaged, could be reassigned to a safer area, but won’t. Arabkhan, who supports not only his but his deceased brothers’ families, hasn’t seen them in months.

This part of Ghazni is second only to Waziristan in terms of danger and the quality of enemy combatant, said Arabkhan.

“I don’t care whether they are good fighters or bad fighters,” he said. “I still want to fight them. I am a warrior, and my place is to lead and set an example for all, especially since the Americans came here to help my country.”

“Our paratroopers are doing a fantastic job under very challenging and arduous conditions,” said Salome. “They live the Army values every day. It is through their example that we see changes slowly begin to occur as the character of the professional Ssoldier shines through all the obstacles that impede progress.”

“It’s working,” said Schneider. “Now if only the ANA can sustain it when we leave.”