The National Reconnaissance Office is 50 years old this month, but its mission of designing, building, launching and maintaining America’s intelligence satellites is always future focused, its chief said yesterday.

Bruce A. Carlson, a retired Air Force general and NRO’s director, told defense reporters here the office’s current missions range from identifying roadside bombs in Afghanistan to tracking activities in China and North Korea.

The National Reconnaissance Office has launched six satellites in seven months, “the best we’ve done in about 25 years,” the director said.

As recently as two years ago, more than 30 percent of the organization’s programs were rated yellow or red for improper performance. All the NRO’s major system acquisition programs are now in the green — delivering on schedule, on contract and on price, Carlson said.

Carlson said NRO’s mission is getting more challenging because space is becoming increasingly congested where the satellites work.

“Other countries are launching a lot of stuff, and it’s becoming more competitive,” he said. “We all have to operate in the same space.”

And it’s no secret the Chinese are becoming more active in space, the director added. “That concerns us because we’re not absolutely sure of their intent,” he said.

NRO and Air Force Space Command have a joint space protection program, Carlson said, which is the “ace in the hole” should “somebody try to do something.”

“We also use the space protection program to work around the congestion problem … make sure we don’t run into something else up there,” he said.

China and Russia both contend with the United States for room in space, Carlson said.

In satellite surveillance as with night fighting, deep strike capabilities and special operations expertise, “they have to focus on our strengths,” the director said.

China and Russia don’t try to compete with U.S. capabilities, but to counter them, Carlson noted. “That’s why we have a space protection program,” he said.

China is a focus for his organization’s surveillance efforts, as is North Korea, Carlson said.

“I remain concerned about [China’s] intent and exactly what it is that I do not know,” he said.

North Korea also works “really hard to deceive us,” Carlson noted. “We work really hard to make sure we don’t let them deceive us. So it’s sort of a cat-and-mouse game. It’s very serious for us.”

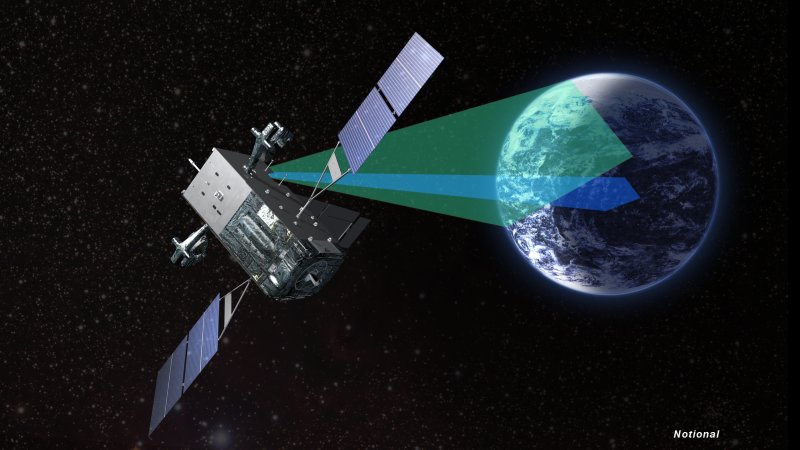

The NRO’s three main lines of business are imaging, signals collection and communications, the director said. The science and technology, or developmental and demonstration program, underlies all three, he added.

“We have a very active program to do our own technology,” Carlson said. “We’re the only organization in the government that does space reconnaissance … and that takes some unique technologies.”

NRO partners with the National Laboratories and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in developing new capabilities, but some 60 percent of the equipment on the six recently launched satellites was developed in-house, he said.

Several other small satellites — less than about 1,000 pounds — are now in orbit demonstrating new technologies that NRO will roll into its existing surveillance systems, the director said.

For imaging reconnaissance, the NRO seeks to examine as many parts of the spectrum with as many instruments as possible, he said.

The goal is to “do sensing … in the daytime, at night, in bad weather, good weather … and sandstorms,” he said.

Some of the signals collection satellites are “remarkably old,” he said.

“Those satellites were designed to collect Soviet long-haul communications that dealt with the Cold War,” he said. “Now they’re collecting phone calls or push-to-talk radio signals out of the war zone.”

NRO uses its communications satellites to relay image or signals data around the world and down to the ground for processing, then shunt the results back to where they’re needed, Carlson said.

“Processing takes a lot of energy and [computer] capacity,” he said. “We’ve got to do that on the ground; we can’t afford to do it in space.”

NRO’s ability to fuse various streams of intelligence data — including image, signals and geolocation — into a single, usable result has increased by an order of magnitude, but is five orders of magnitude below where it needs to be, Carlson said.

“It’s incredibly difficult to take a picture someplace and fuse it with signals intelligence, that you might have a million pieces of, and sort that all out and geolocate it rapidly,” he said. “But in many cases we’re able to do that … in minutes or less.”

One promising example of fusion is the “red dot” system, Carlson said, which pinpoints the signals emitted by roadside bombs set for electronic detonation.

“We do a lot of work to make sure that we know what those signals are, where they’re coming from, and geolocate them,” he said.

That data generates a red dot on displays in military vehicles or command posts to show high probability of an explosive, he added.

“I can’t tell you exactly how we do that, but it’s a pretty clever set of technologies,” the director said. “What it has meant is that, even though we still have an unacceptable loss from [roadside bombs], we are catching a lot of them before they’re detonated.”

The system has been in place for approximately six months and has been about 80 percent effective, he added.

NRO was also “instrumental” to the NATO operation in Libya, ensuring the air campaign was successful, Carlson said.

The NRO feeds data to military commanders, he said, but it is also a key strategic asset, serving the National Security Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

There will always be competition between, for example, the information an analyst wants to assess foreign weapon systems and a combat commander’s need to know where and how many cell phones are operating in a particular enemy area, the director noted.

Whether identifying insurgent behavior patterns or focusing on larger national security questions, Carlson said, “My job is to … get the most out of a sensor.”

There are only so many satellites in orbit, so NRO has an inclusive and responsive process to allocate its 24-hour capabilities, he said.

“What that allows us to do is very rapidly … worldwide and throughout our architecture, tune those systems,” he said.

An example is an aircraft bailout requiring a search-and-rescue effort, he said.

“We can, within a matter of seconds, turn an incredible number of our sensors on a specific area,” he added.

Carlson said during NRO’s next 50 years, the challenges are to do what it now does even better, and to develop more in-space capability.

“We know what we have to do — we have to provide the best, integrated intelligence in the world,” he said. “Now, [we have to] do it faster and cheaper.”

Space satellites have always focused downward, and now need to be able to look around and up as well, he said.

“Because space is more congested and more contested and more competitive … we’ve got to build systems that continue to be much more adaptable,” he said. “Space reconnaissance — that’s my job.”