With the success of a forward-firing miniature munition, also known as Spike, the Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division (NAWCWD) proved that the government, by owning and controlling a weapons design, using modern modular designs and commercial-off-the-shelf components through ‘non-Department of Defense’ U.S. companies, can procure and deliver sophisticated guided missiles at a much lower cost than it is currently experiencing.

Spike was conceived, designed, developed and tested at NAWCWD. To date, about 26 advanced development all-up test missiles have been built and tested by the NAWCWD team. More than 10 successful full-scale guided missile tests have been completed. The most recent success was a counter-unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) demonstration in June 2013.

The idea for this demonstration began in 2012 at an annual counter-UAV exercise at NAWCWD Point Mugu, in which the Army Research and Development Engineering Command (ARDEC) from Picatinny Arsenal was one of several participants. Picatinny Arsenal is the Joint Center of Excellence for Armaments and Munitions. Located in New Jersey, it provides products and services to all branches of the U.S. military, and specializes in the research, development, acquisition and lifecycle management of advanced conventional weapon systems and advanced ammunition.

The Picatinny team was demonstrating the Palletized Protection System (PPS) which used a radar to detect airborne and ground-based targets and cue a mounted camera during the exercise. Discussions between engineers from NAWCWD and ARDEC led to the idea of putting a missile, Spike, in that loop to provide a tactical capability to actually engage the targets detected.

After further discussions, NAWCWD signed a memorandum of agreement with ARDEC. Plans were put together in the spring and the integration of Spike with PPS was successfully demonstrated in the summer on the land range at NAWCWD China Lake against an airborne target. Greg Wheelock, a NAWCWD technical lead, said this demonstration proved that ARDEC could have a potential new kill mechanism to accomplish their counter-UAV mission.

“The fact that Spike was developed by the Navy and is government-owned makes it even more attractive because we have the ability to quickly modify the system to meet their specific requirements,” he said.

Wheelock said NAWCWD continues to work with the Army to refine requirements. Depending on what traction the Army gets with securing funding, the team stands ready to continue developing the capability.

“In today’s budget-constrained environment, a collaborative effort is more likely to be successful than trying to go it alone,” he said.

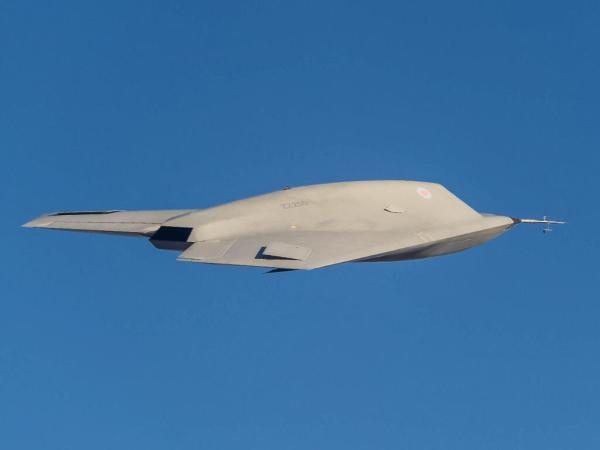

Spike is a multi-purpose system that can be launched from the ground or the air, and is being developed to be shoulder-fired. Several Spike missiles can also been loaded on a single mount to engage multiple targets.

Wheelock admits Spike is not a one-missile-fits-all but said there are several capability gaps for which Spike would be a good fit.

One such area, and an increasing threat, is that of small boat swarms often referred to as the fast attack craft (FAC) and fast inshore attack craft (FIAC) threat. One strategy the enemy employs is to use multiple FACs/FIACs to go after a target. The NAWCWD team has demonstrated that Spike could be a good gap-filler in a layered defense against this tactic.

“With a number of targets coming at you, there’s potential for some to get through,” Wheelock said. “Spike is a good option for taking out those leakers. It’s not going to blow those boats out of the water but it can take the boat out of commission. What we lack in warhead size is compensated for in accuracy, and we have the ability to put that charge where it will have the most effect.”

Spike has recorded direct hits against moving FIAC threats in separate test events on the NAWCWD Point Mugu sea range.

Even though the Spike project has logged many successes in its relatively short existence, Wheelock and his team continue to seek new ways of improving the missile. Right now, they are focused on redesigning Spike so it can address current threats. One redesign element involves going from a fixed wing and canard rail-launched system to a folding control surface, tube-launched capability. Wheelock said he sees value in moving to a common tube system that would accommodate all launch options so the missile doesn’t have to change configurations. The team is also looking at upgrading Spike’s seeker to address obsolescence issues and to improve image processing capability.

The ultimate goal is to field Spike either as a program of record or through a rapid development and delivery effort. Wheelock said his core team of about 10 is expandable to meet the requirements, and limited rate production could even be done in-house at NAWCWD China Lake.

“We own the technical drawing package, we own all the intellectual property, we have the capability to develop it, take it out on the range, test it, come back and tweak it, and go back to test it and do limited rate production right in our own backyard,” Wheelock said. “Very few places can do that; that capability and flexibility means improved response time to warfighter requirements.”

Spike is not just a potential force on the battlefield; it’s also a proven catalyst for workforce development and growth. More than 200 entry level engineers and scientists have worked on the Spike project as part of Section 219 of the FY 2009 National Defense Authorization Act that enabled mechanisms to provide funds for defense laboratories for research and development of technologies for military missions.

“At NAWCWD this legislation has been instrumental in both developing and demonstrating new warfighting capabilities and it has been a critical means in rebuilding and honing the Navy’s technical workforce for the future,” said Scott O’Neil, NAWCWD executive director. “Placing experienced subject matter experts as mentors and team leads to new science, technology, engineering and mathematics professionals working on projects designed to forward critical technologies or to develop systems that have real application or military merit was the underpinning strategy for NAWCWD’s 219 program.”

NAWCWD used the 219 program together with the Spike project to focus on workforce development by bolstering critical at-risk skills and developing newly required skills by doing hands-on development and technology generation. Using the 219 program, young engineers and scientists worked on the Spike project and developed not only technical but also project management skills.

“Becoming a weapons engineer is a learned skill; you don’t come out of school with those qualifications,” Wheelock said. “The only effective way to learn is to do it. A project like Spike under the 219 program gives young folks the opportunity to actually work on a real system that has the same requirements, undergoes technical reviews and, and has the same stringent oversight as any other weapons development program.”

Another benefit of the union between the Spike project and 219 resources is the resulting pipeline of qualified folks to support the technical project offices and programs of record.

“Even if someone doesn’t become a weapons engineer, they can take the rigorous attention to detail and the system engineering practices they learned here and apply them wherever they are,” Wheelock said.

Though Spike has been successfully demonstrated against a myriad of fixed and moving targets at sea, on land, and in the air, the NAWCWD team continues to look for innovative ways to hone the design and add capability. Spike is still in development today but, according to NAWCWD leadership, it could be rapidly deployed and would help provide U.S. and allied warfighters with an unfair advantage.