A huge submarine deal is on the table this week when Japan and Australia meet to shore up their military relationship, as the security architecture of the Asia-Pacific shifts to meet the challenge of a rising China.

Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida and Defence Minister Itsunori Onodera will play hosts in Tokyo on Wednesday to Julie Bishop and David Johnston, their respective opposite numbers, for the fifth round of so-called “2+2” talks.

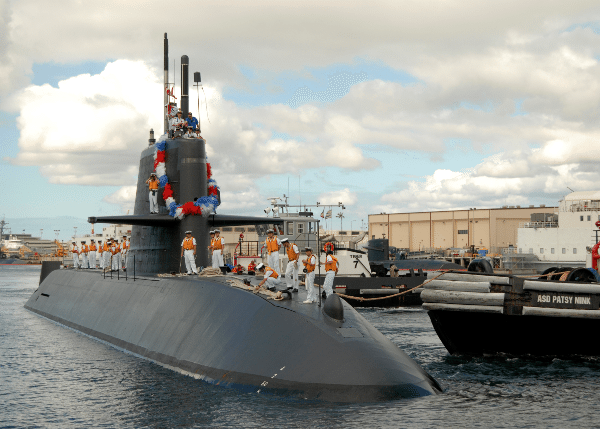

High on the agenda will be discussions on the transfer of Japanese submarine technology to Australia, with Canberra needing to replace its fleet of stealth subs over the coming years at a reported cost of up to US$37 billion.

This could see Tokyo’s technology — or even entire Japanese-built vessels — used in the fleet, in a deal that would yoke the two nations together for several decades, binding their militaries with shared know-how.

The expected step comes as China’s relentless rise alters the balance of power in a region long dominated by the United States, with Beijing ever-more willing to use its might to push territorial and maritime claims.

A rash of confrontations in the South China Sea has set off ripples of disquiet in the region, as has the festering stand-off with Japan over islands in the East China Sea.

The worries have encouraged a relationship-building drive across Asia, with Australia and Japan — both key US allies — a notable pairing.

Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe signed a free trade pact and a security deal in April.

Following an Australian request, Tokyo will let Johnston see Japanese submarines during his stay, Onodera said.

The Japanese defence chief also stressed that various “frameworks” — military pacts — grouping Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United States are vital in ensuring security in East Asia.

Abe’s military push

Abe looks to nudge long-pacifist Japan towards a more active role on the global stage, including loosening restrictions on when its well-equipped armed forces can act.

He has also relaxed a self-imposed ban on weapons exports, giving its high-tech weapons makers a leg-up in the global marketplace.

Japan Inc. has hailed Abe’s promotion of the nation’s military industry, which some see as just another plank in his economic push to boost the nation’s heavy manufacturers and exporters.

However, some analysts suggest it is more nuanced.

Koichi Nakano, political science professor at Sophia University in Tokyo, says Abe’s beefing up of military industry shows the prime minister marrying his twin aims of economic and diplomatic rejuvenation.

“The Abe government may be hoping that they can have a tacit understanding with the Abbott government which is also a conservative regime,” and raise pressure on China, he said.

Observers point out that a more competitive arms industry would be more able to meet future domestic demand in the event that Japan’s military finds itself in need of more firepower.

China’s military has received double-digit budget increases for several years and analysts say its capacity is building towards its ambition of having a blue-seas navy — one that is able to push the US out of the western Pacific.

The US, in response, has looked to bolster its military capacity in the Asia-Pacific, placing or realigning troops in Australia, Japan, the Philippines, Hawaii and Guam, and trying to thread its friends together.

Abe, for his part, has courted members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), offering coastguard vessels to Vietnam and the Philippines. Both have proved willing to push back against Chinese claims in the South China Sea.

Increasingly, the outlines of a nascent coalition are becoming visible, says Takehiko Yamamoto, a security expert and emeritus professor at Waseda University.

“Naturally, Australia finds Japanese technology attractive,” he said, adding that the nation’s prowess in precision-manufacturing for the highly sophisticated submarine kit was enviable.

Tighter ties between the two US allies, both with vast coastlines, are a part of a greater “security complex”, also involving New Zealand and India, that serves to create a counterbalance to China, said Yamamoto.

“It is a part of a long-term trend,” he said.