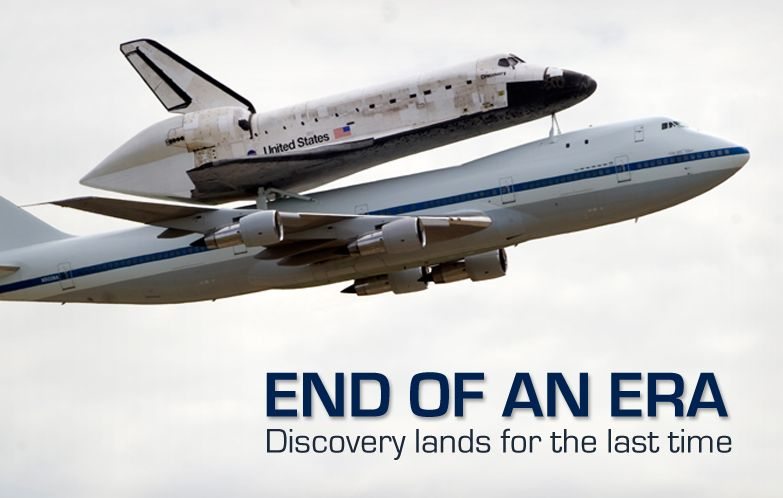

After almost 27 years and 39 flights in Earth’s orbit, the space shuttle Discovery arrived at Dulles Airport in Washington, D.C., April 17 on its way to its final resting place.

The last moments in the air for Discovery began at Kennedy Space Center, Fla., mounted on top of a modified Boeing 747. The retired spacecraft will take final residence in a hangar at the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center April 19, in Chantilly, Va.

At its new home, Discovery will stand on the same spot the shuttle Enterprise occupied since the center’s opening in 2003, according to Dr. Valerie Neal, the curator at the National Air and Space Museum. Unlike Discovery, Enterprise was only a test vehicle and was never used for space flight, making it a less significant artifact to experts. Therefore, it was moved to the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum in New York.

On duty since 1984, Discovery was the third orbiter that was built and is now the oldest shuttle remaining in the fleet.

“Because it started service so early, it flew all different types of missions shuttles were assigned,” said Neal. “In our view, it’s the champion of the shuttle fleet and really helps tell the story of the shuttle era.”

Most visitors will be shocked by the immense size of the orbiter, which on TV often seemed dwarfed by its external tank and booster rockets, Neal said. Others may wonder about the shuttle’s outer condition. Its exterior is well worn and the black tiles of its heat shield show the scars that earth’s atmosphere inflicted.

“We asked NASA not to clean the exterior or repaint it,” Neal said. “We wanted Discovery to be as it was after it flew its last mission.”

Changes to the orbiters were minor, Neal said, but included required deinstallation of maneuvering pods, which contained traces of hazardous fuels, and the removal of the shuttle’s main engines, which NASA is planning to reuse in the future.

As the shuttle takes its place among the Enola Gay and other iconic aircraft, it also puts a close to a chapter of Air Force history.

“The intention in the 1970s was to put all missions, civil and military, on the shuttle once it became operational,” said Rick Sturdevant, the deputy director of history at the Air Force Space Command. “It was supposed to become the only launch vehicle for the U.S., but a lot of Air Force personnel doubted it was a good idea to put all of our eggs in one basket.”

“However, as the shuttle approached, Air Force planning intensified with the construction of a shuttle launch complex at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., and a Shuttle Operations and Planning Center at Shriever Air Force Base, Colo.,” Sturdevant said. “One of the primary reasons for the creation of what was later to become Air Force Space Command was the intention of administrating and planning shuttle operations for the Department of Defense.”

While much of these installations were never used to full capacity, the Air Force provided services, such as range support during launches and tracking of orbital debris in protection of the shuttle.

Sturdevant said he believes the shuttle caused Air Force leadership to think more operationally about space and what the Air Force could do to use space in support of war-fighting capabilities. The shuttle was supposed to become essential in transporting those war-fighting assets into orbit.

Sturdevant said he believes the shuttle caused Air Force leadership to think more operationally about space and what the Air Force could do to use space in support of war-fighting capabilities. The shuttle was supposed to become essential in transporting those war-fighting assets into orbit.

“For 30 years, it was the premier aerospace vehicle in the world,” said Tom Jones, a former shuttle pilot. “It was the most complex machine ever built and had capabilities in space that have yet to be matched, thirty years after it came onto the scene.”

The shuttle established a semblance of routine space flight, Neal said. Space flight seemed like it was no longer going to be extraordinary, but that it was becoming a normal enterprise of the United States.

Two of the originally five sister-ships were destroyed during operations. In 1986, Challenger exploded shortly after take-off, and in 2003, Columbia was torn apart during re-entry into earth’s atmosphere. During both accidents, all seven crew members were lost.

“In many ways, the orbiter left a bitter taste in the mouth of many senior Air Force officials,” said Dwayne Day, a senior program officer with the National Research Council. “It helped develop a number of important technologies, and delivered numerous important scientific and national security payloads.”

“In many ways, the orbiter left a bitter taste in the mouth of many senior Air Force officials,” said Dwayne Day, a senior program officer with the National Research Council. “It helped develop a number of important technologies, and delivered numerous important scientific and national security payloads.”

But the military did not get as much out of the program as hoped, and stopped DoD shuttle operations after the Challenger tragedy.

“People died in very public ways,” said Day, who worked on the Columbia accident investigation board in 2003. “There were no ejection seats, no escape pods,” Day said. ” If the vehicle was damaged, the crew was doomed. It was a bad situation.”

“The shuttle educated the military about having a distributed way of getting into orbit,” said Jones. “Challenger only exposed the vulnerability of having only one way of getting your payloads into space.”

The Air Force quickly responded and broadened its base, said Jones.

“What the orbiter did gain for the military was cutting-edge experience on human operations in space,” explained Jones. “Now, with the classified X 37, which is sort of a derivative of the shuttle, the Air Force is taking full advantage of the lessons learned.”

It took a lot more maintenance than was anticipated, said Neal, and maintenance took a long time in between flights, so the shuttle never deployed as routinely as desired.

“It was a very expensive vehicle,” said Day. “It was so expensive that it made it difficult to find funding to develop a replacement vehicle.”

Retired Air Force Col. John Casper, a former shuttle pilot, said the shuttle lasting legacy will be its contribution to building the International Space Station.

“Sixteen different nations are involved, forming what is often called the largest international program since the cooperation of the Allies in WWII,” said Casper. “Another legacy is the Hubble Space telescope, which the shuttle carried into orbit.”

For Casper, the transition, from an Air Force squadron to the astronaut corps, was an easy one.

“There is real joy in working as a team and experience tremendous teamwork with people that are very dedicated, very much like it was the Air Force,” said Casper about shuttle crews. “It was a talented, educated and disciplined team, that was very passionate about what they do.”

Like many missions in the Air Force, shuttle operations called for precision, professionalism and complete immersion in the job, said Jones.

Memories of experiences with the shuttles will always stay with the astronauts, they said.

“To look down onto our home – this great, beautiful planet – was very fulfilling,” said Jones. “It is so lovely that tears came to your eyes when you get a chance to reflect upon what you are seeing.”

For Casper, flying the shuttle was unlike anything possible on earth.

“The shuttle was not like a fighter. The only time you really flew it like a plane was the landing,” said Casper. “And then it could only glide back to earth. There was no way to try the landing again – you only got one chance.”

After the Columbia accident, Casper became NASA’s Mishap Investigation Team’s deputy for the debris recovery operation. While the nation was in shock, he said he lost friends.

“The community of astronauts is very small. We all know each other. Some even flew together in the Air Force,” said Casper. “I guess it was also in the Air Force that you find out what happened, try to correct the problem and get back to the mission.”

“You can’t let it stop you,” said Casper. “You can’t stop flying planes in the Air Force and you can’t stop exploring in space.”

But the shuttle mission is over and new technology is needed to move onto bigger and better things, said Casper. But a certain sadness remains for the astronaut and space enthusiasts alike.

“Most shuttles have about 25 to 35 flights,” said Casper. “But they were built for 100 flights each. So they’re in pristine shape.”

Thinking that the shuttles were old and decrepit is a common misconception, said Neal.

“The fleet has, in fact, been constantly updated, to the point that the shuttles that flew in 2011 were hardly the same as in 1984,” said Neal. “It was the same airframe, but a lot of the technology inside was new,” said Neal.

For Casper, now an assistant for program integration for NASA’s Orion program, a strong space program is an essential political and military tool of the future, he said.

“Venturing into space is a demonstration to the world that we have the ability and the will to do so,” he said. “It is a necessary extension of aerospace power and the Air Force’s mission.”

One important mission for the shuttle will continue even at the museum – it will continue to inspire.

“Seeing the U.S. Flag hanging on the hangar wall behind the shuttle, just like it did when it was in its assembly and servicing hangar, you realize that the shuttle is an icon for the United States,” Neal said.

Neal’s team wanted to make the arrival at the museum as accessible as possible, she said. The transfer from NASA was free to the museum and seeing the shuttle will be free to the public -after all it was the public that has supported and financed the shuttle program all along, Neal insisted.

“This is the spacecraft of your generation, it is an American icon.” said Neal. “If you never made it to a launch or landing, you really owe it to yourself to see how the U.S. went into space during your lifetime. Come and take pride and ownership in it.”

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is located a few miles south of Washington Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Virginia. It is open from 10:00 am – 5:30 pm seven days a week, with the exception of Christmas Day. Admission is free, parking is available for a $15 fee.