With Ukraine dependent on Western military aid following Russia’s invasion and Moscow burning through stocks and under sanctions, both sides fear exhausting their shells, bombs and missiles, experts say.

Moscow’s economic exclusion means it is “having to buy artillery rounds from North Korea”, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby told reporters recently, pointing to deals for “millions of rounds, rockets and artillery shells”.

Meanwhile Britain’s Ministry of Defence said this week it “is likely that Russia is struggling to maintain stocks” of drones. Sanctions make it difficult for Moscow to obtain the vital components needed to replace drones destroyed in combat.

The Kremlin has reportedly struck a deal to buy drones from Iran.

Both Western governments and Kiev say the invaders are suffering from serious logistical difficulties.

Precision strikes with high-tech Western weapons are undermining Russia’s ability to fight and Moscow is turning to outdated arms as its stocks of more modern gear run down.

‘Mystery’ of Russian stocks

“It’s a mystery what the Russians have left,” said Pierre Grasser, a researcher associated with Paris’ Sorbonne University.

“They had enough supplies for their original plan.

“But the fact is that the war is lasting longer than expected and the destruction of their reserves by US-made HIMARS rockets is reshuffling the deck,” he added.

“Moscow doesn’t have many allies that can supply it or come to the aid of its manufacturers. China still refuses to get involved beyond the diplomatic field.”

As for the isolated Communist regime of North Korea, “there’s likely to be a limit to what Pyongyang can give — just enough to refill the stocks for a few weeks”, he said.

Last week, French researcher Bruno Tertrais of the Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS) said “the chances of Russian military fatigue are much higher than Ukrainian military fatigue”.

But Kiev continues to request weapons and ammunition from the West — which itself may be reaching the limits of its capacity.

On Thursday, the United States said it would supply another $675 million in military equipment.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin made the announcement in Germany, where Ukraine’s allies were meeting to discuss coordinating their deliveries.

Washington has also said it will provide a further $2.0 billion in loans and grants for Ukraine and its neighbours to buy US military gear.

This is on top of the $4.0 billion it authorised in the fiscal year that ended in June.

No new EU pledges

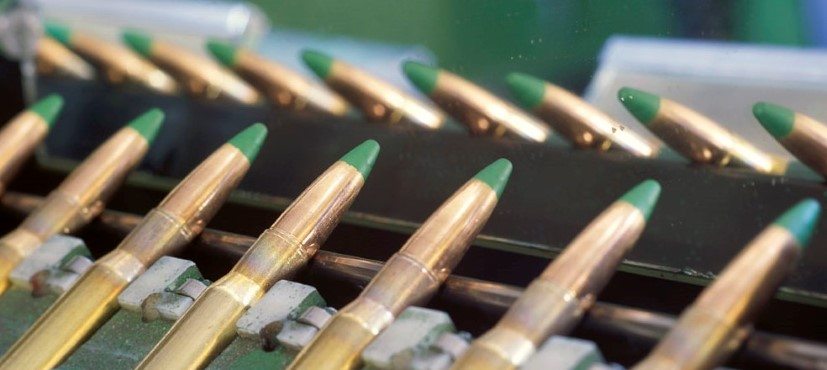

Social media accounts specialised in identifying weapons have spotted Pakistani and Iranian shells being fired by Ukrainian artillery, suggesting that Kiev has built multiple supply chains for its troops.

But the Germany-based Institute for the World Economy (IFW) said last month “the flow of new international support for Ukraine … dried up in July”, with no new pledges from major European Union countries like Germany, France or Italy.

On the other hand, the IFW noted that more countries were finally coming through with their promises of aid for Kiev.

NATO countries have supplied almost half a million shells for the roughly 240 155-millimetre guns they have sent Ukraine to replace Soviet weapons whose ammunition has been used up, Grasser said.

“Since July, they’re being used up at a rate of 3,000 shells per day. Technically, Ukraine can keep going until the start of winter,” he added.

“However, beyond that there are some questions about how much NATO can supply.”

Weight of cash

Given the relative strengths and losses of the two sides, Western aid to Ukraine is well short of what is needed to win the war and replace destroyed equipment, said Andrei Illarionov, a former economic advisor to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Illarionov, who now works for the US-based Center for Security Policy, said that during World War II, the Allies only really began turning back the Axis in 1943, once their spending outweighed their opponents’.

“The military aid delivered to Ukraine is not more than $3.0 billion per month. Overall expenditure (by) Ukraine plus the coalition looks like $7.0 billion a month,” he said last week at a Bucharest event organised by the New Strategy Center think-tank.

As for Russia, “different estimates have been given recently — between $500 million and $900 million a day — which means $15-27 billion a month”, he added.

“In the war of attrition, the crucial underlying factor (for) who might win the long war is the ratio in military expenditure”.

“In military terms,” Grasser said, “the two sides are evenly matched. The Ukrainians have fewer weapons than the Russians but they’re now much more accurate.”

But, he noted, “In its favour, Moscow has access to vital raw materials for the war effort.”

“We’re entering a period of unstable equilibrium. Whoever launches one counter-offensive too many is likely to lose the battle of attrition.”