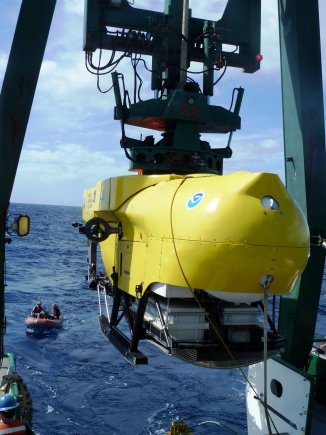

Five miles off the southern coast of Oahu, Hawaii, a three-person submersible was lifted off the back of a boat by a mechanical crane. The underwater vehicle floated on the surface of the ocean for a few moments as the crew in the chase boat unhooked the submersible as it prepared for its 550-meter journey into the depths of the ocean.

Crisp light blues faded slowly into darker shades of color, and the temperature grew colder in the vast blackness. Even with the underwater lights, the researchers inside could only see 20 meters in front of them, through portholes barely as big as their faces.

One of those researchers was Mike Knudsen, the field remediation air monitoring manager for the Chemical Biological Application and Risk Reduction, or CBARR, Business Unit of the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center. Knudsen was part of a CBARR team that supported a multi-phase research effort called the Hawaii Undersea Military Munitions Assessment, known as HUMMA, to investigate sea-disposed military munitions along the Hawaiian coast.

“A typical dive is between eight and nine hours in a small metal sphere that is seven feet in diameter, and there are three people in there,” Knudsen said. “It was a small, cold space. But an absolute, can’t-pass-up-opportunity. I was excited.”

According to the HUMMA project website, both conventional and chemical munitions were discarded south of Pearl Harbor following World War II, including 16,000 M47A2 100-pound mustard-filled bombs. For two weeks beginning on Nov. 23, CBARR supported its second mission for HUMMA, and provided chemical analysis for nearly 300 samples collected by the submersible, including 165 sediment samples, five water samples and 36 samples of shrimp tissue.

“Our job on the dive was to provide chemical warfare material sampling expertise and to help locate items on the bottom of the ocean. One of the big pieces of the job was to watch the sonar to make sure the sub doesn’t run into things or get snagged on other hazards,” said Knudsen, who has made a total of six dives down in the submarine.

Old munitions deteriorating on the sea floor decorated the muddy sediment like railroad tracks on the sonar map. There are no plants at these depths and few animals, but every once in a while the crew caught a glimpse of a shark or sting ray. Knudsen attributes the sightings not to luck but to the bait traps used by the submersible to catch shrimp for bio analysis.

John Schwarz, CBARR analytical chemistry laboratory manager and project lead, took the equivalent of a mobile analytic platform and stationed it on a boat in order to analyze the collected samples. A glove box was used for sample preparation and MINICAMS accurately monitored air inside the designated laboratory space. All equipment in the designated onboard laboratory, including computer monitors, had to be tied down due to the ship’s movement on the ocean surface. Schwarz said the experience was more unique than anything else he’s done for CBARR.

“On the ship we were able to successfully execute the quality of analytical procedures and protocols for samples as we would in our fixed laboratory back at our headquarters at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland,” Schwarz said. “To me that’s why it was a big achievement. We did it on a boat in the ocean.”

While Knudsen and CBARR teammate Jim Swank, the designated explosive ordnance disposal technician of Pine Bluff Arsenal’s (Ark.) Field Technology Branch, spent their days in darkness underwater, Schwarz spent his nights working in the laboratory analyzing samples and clearing them of chemical agents.

According to Schwarz, the munitions themselves are too dangerous to lift from the ocean floor and are unlikely to wash ashore due to the depth of their location, where the water temperature hovers around the 40-degree Fahrenheit mark. The possible chemical agent inside the World War I-era weapons would be frozen at that temperature. But there was one thing that was curious about the munitions, Schwarz said. They were home to an increased population of Hawaiian Brisingid sea stars that made the deteriorating munitions a natural habitat. During HUMMA, a few sea stars were collected and sent to Smithsonian scientists to study.

CBARR was first brought onto the research team as chemical experts in 2009; two years after the HUMMA project began. The research effort is funded by the U.S. Army and led by the University of Hawaii to investigate the environmental impact of the sea dumped munitions on the surrounding environment. During that time, prime contractor, Environet, and the University of Hawaii mapped the ocean floor and used the Pisces submersible to collect samples within 10 feet of munitions.

“The Army considers this research effort extremely important to both helping close data gaps in DOD’s understanding of the effects of chemical munitions in the ocean environment and helping validate and improve upon procedures developed for investigating sea disposal sites, particularly those in deep water,” said Hershell Wolfe, the deputy assistant secretary of the Army for Environment, Safety and Occupational Health, in a November press release.

Wolfe recognized Schwarz and the CBARR team in a letter of appreciation dated Jan. 10, 2013, citing “a selfless willingness to duty by working nearly around the clock in support of HUMMA’s demanding mission goals.”

University of Hawaii Principal Investigator Margo Edwards, Ph.D., shared a similar sentiment for CBARR’s efforts. In a press release, she stated, “UH’s partnership with the U.S. Army and Environet significantly increased Hawaii’s and the world’s understanding of sea-disposed munitions: how they were disposed in the past and how they have deteriorated right up to the present time. The forthcoming field program will hopefully allow us to expand our understanding of the potential environmental impact of munitions that may contain chemical agent, and develop methods for monitoring and modeling future deterioration.”

The Army and University of Hawaii are finalizing the research report for their latest mission. The next phase of the project will evaluate performance differences between human-occupied submersibles and remotely operated vehicles, and also test new sensors and instruments that will improve the visual mapping and sampling of the munitions.