President Obama’s newly-unveiled Afghan strategy calls for a quick infusion of U.S. troops to fight the Taliban and to train Afghan security forces, followed by a withdrawal of American forces starting in as early as mid-2011. That is a less ambitious undertaking than the administration envisioned 10 months ago.

The new Afghan strategy, say analysts, is largely a refined but less ambitious version of an earlier policy review President Obama ordered after his election and released in March.

But as former State Department policy planner Daniel Markey points out, there were still too many unknown factors and unanswered questions to satisfy the president.

“The March review did not answer some very big questions about resource and timeline,” he said. “And so now the administration has at least a preliminary answer on both of those issues with respect to troop numbers and kind of general outline on how long they intend to pursue this strategy, that it is not open ended, this 18 month number, but maybe also it is not a firm deadline for getting out,” he adde.

The earlier strategy called for a surge of civilian workers to assist Afghanistan in building institutions along with stepped up training of Afghan security forces. There was talk of a regional approach to fighting insurgency and terrorism.

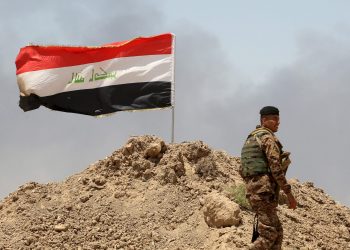

Former Taliban fighters gather at a police station after surrendering to US and Italian soldiers in western Herat, Afghanistan, Saturday, 21 Nov 2009

Now, talk of nation-building is gone, and there are no specifics, at least publicly, of how to get Pakistan more engaged into the fight against al-Qaida, which has safe havens in Pakistan. The goal of defeating the Taliban, advocated by some in the administration, has been ratcheted down to degrading the insurgency’s ability to challenge the government. But 30,000 more troops will be deployed until a controversial exit date.

Christine Fair of Georgetown University, who has long experience in South Asian affairs, says the earlier review was glossed over in the president’s unveiling of his latest incarnation of Afghan policy.

“What he did not say explicitly is that we have really scaled down our ambition from the March 2009 White Paper,” she explained. “So some of the more capacious goals of state-building were absent in this. But he is such a sophisticated, subtle interlocutor that the way in which this current strategy goes forward does differ in substantive ways from the March ’09 plan. And it would have been nice if he had explicitly said this,” she said.

At a congressional hearing after the new strategy was unveiled, Defense Secretary Robert Gates said he was concerned the earlier strategy seemed to emphasize nation-building over U.S. security concerns.

“One of the elements of the dialogue that we have had inside the administration for the last three months is, how do you know that mission and make it more realistic? How do you communicate that what this is all about is really our security?” He asked.

Afghanistan’s Ambassador to the United States Said Jawad says he is not upset that the issue of nation-building was passed over because it was largely a myth anyway.

“Frankly, nation-building in Afghanistan has never been carried out. It has been talked about, it has been a slogan,” he said. “But Afghanistan has been the most under-resourced mission in any post-conflict country. So we do not mind if you do not speak about it because it was never implemented,” he said.

Afghanistan’s President Hamid Karzai greets guards of honor as he arrives to the Presidential Palace for his inauguration in Kabul, Afghanistan (File)

But there was reported to have been much internal discussion of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, who won a second five-year term in a controversial presidential election in August marred by widespread electoral fraud. Daniel Markey, now with the Council on Foreign Relations, said the perception that he was about to lose U.S. support, whether real or imagined, pushed Mr. Karzai into alliances with corrupt characters.

“It sent him looking for other allies – powerful political players within Afghanistan who would back him up in this moment of uncertainty with respect to what Washington was trying to do,” he said. “And that actually ended up being counterproductive from a U.S. perspective because the people that he went to were some of the most tarnished former warlords and so on who Washington hoped to rule out of Afghan politics, not rule back in,” said Mackey.

A number of analysts, including the ambassador, were struck at the comparatively scant attention paid to Pakistan in the new strategy, at least publicly. Some analysts suggest that U.S. officials do not want to turn the spotlight too much on that quarter because cooperation between Washington and Islamabad is deeply unpopular in Pakistan, and much of that cooperation is covert.